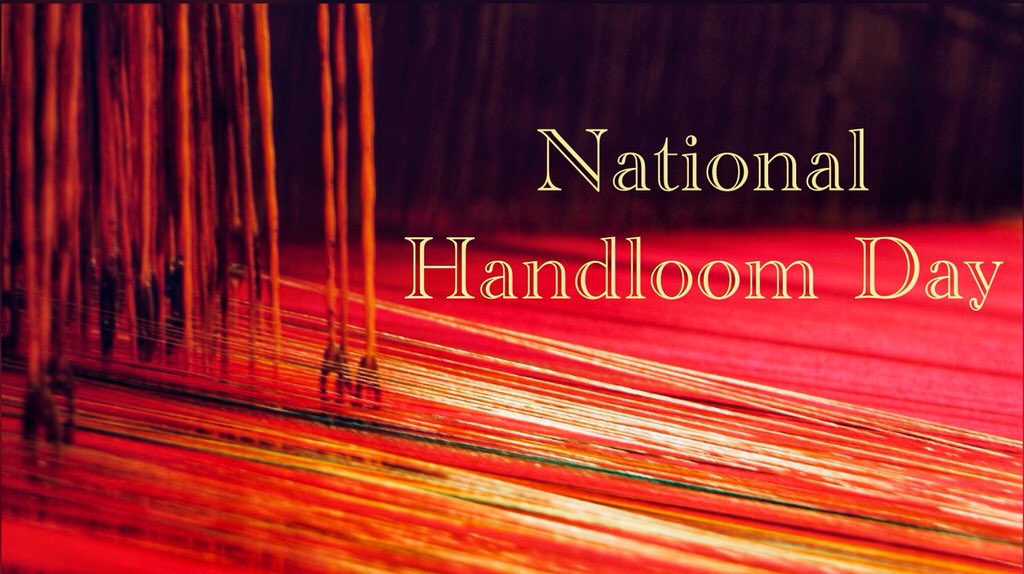

When human hands and heart work in rhythm, the threads that they intertwine define their identity.

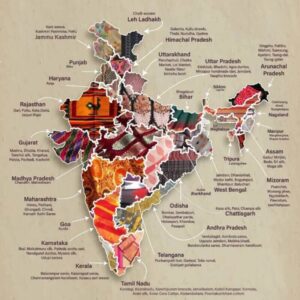

India is defined through its origins of rich culture. Yoga, Ayurveda, chess, board games, and even buttons are among the many accomplishments and honors this enormous, stunning country has received. But there is still one aspect of India that stands out the most in this seemingly endless splendor: its textile. We are all aware of the numerous ways in which Indians dresses differ from the Westerners. And the majority of this variance can be attributed to how our fabric was produced and used.

Tracing the History of Handloom

Indian clothing was woven on handlooms for the longest time, until the British introduced their eventual demise. It is believed that the Indus Valley civilization, whose textiles were sold to far-off regions like China, Rome, and Europe, is where the origins of Indian handlooms can be found.

Indian clothing was woven on handlooms for the longest time, until the British introduced their eventual demise. It is believed that the Indus Valley civilization, whose textiles were sold to far-off regions like China, Rome, and Europe, is where the origins of Indian handlooms can be found.

Nevertheless, it was well known that the majesty and prestige of our handcrafted goods were out of this world. Every hamlet in India has a weaver who, along with others, creates the highest-quality textiles. Given how thriving the handloom industry was, it is regrettable to acknowledge that during the colonial era, Indian handloom production was greatly diminished and experienced a sharp fall.

Looking into its Significance

The origin of National Handloom Day can be traced back to the Swadeshi Movement of 1905. This movement was aimed at boycotting British goods in favor of Indian-made products, and handloom textiles were one of the key products that were promoted during this time.

The Government of India officially designated August 7 as National Handloom Day in 2015. The day is now celebrated all over India with a variety of events and activities.

The Government of India officially designated August 7 as National Handloom Day in 2015. The day is now celebrated all over India with a variety of events and activities.

The importance of National Handloom Day can be attributed to many factors. First, it is a day to honour India’s centuries-old handloom weaving culture. Second, it provides a chance to recognise the important role handloom weavers play in the Indian economy, where they employ millions of people. It also promotes sustainable fashion because handloom textiles are made using natural fibres and conventional methods that have little influence on the environment.

Weaves of Garvi Gujarat

Gujarat, popularly known as the Manchester of the East, is a state in India with a long history of textile trades. The state’s cultural legacy is most abundant in the arid Kutch region. However, there are a few other regions of the state that are particularly well-known for their textile crafts. Here are a few textile and weaving traditions from the state.

Patola of Patan

“Chelaji re, mare hatu Patan thi Patola mongha lavjo.” Even the famous Gujarati folk song celebrates the handloom! The distance between Patan, the house of Patola, and Ahmedabad is 125 kilometres.

History: King Kumarpal of the Solanki dynasty, who at the time ruled Gujarat, portions of Rajasthan, and Malwa, sent about 700 Salvi craftsmen from modern-day Karnataka and Maharashtra to his court in his kingdom’s capital, Patan, about 900 years ago. These artisans, who worked in Jalna in Southern Maharashtra, were regarded as the best Patola artisans.

Design: The designs used in Patola include shikhar (the square) which denotes security. Elephant, parrot, peacock, kalash and humans are also used extensively. All these designs are symbolic of saubhagya or good luck for women.

Design: The designs used in Patola include shikhar (the square) which denotes security. Elephant, parrot, peacock, kalash and humans are also used extensively. All these designs are symbolic of saubhagya or good luck for women.

Distinctiveness: Patola textiles were only available to members of a particular social class. Naturally, no one could afford to acquire it due to its exquisiteness and cost. As a result, Patola saris rose to prominence in Gujarati culture. To foster goodwill, Patolas were also given to monarchs and monks. Previously, it was only worn on particularly auspicious occasions.

In Indonesia, Patola rose to prominence throughout the 15th and 16th centuries. There, wearing Patola is something that Indonesians take great pride in. They refer to it as “the cloth of Ma’a” or “mawa,” which means “a cloth made by the god.”

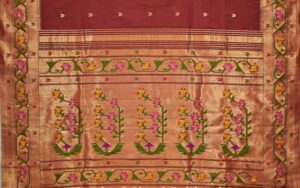

Asavali of Ahmedabad

The Asavali saris get their name from Asha Bhil, an 11th century ruler of Ahmedabad.

History: The historical citations date back to the 16th century. Asavali fabrics were produced by Khatris and Patels, and it is thought by some that the migration of Gujarati weavers had an impact on the brocade traditions of Benaras.

Design: Instead of the more common weft insertions, circular patterns known as buttis are woven into the field as warp, making them distinctive. When the saree is worn, the buttis look horizontal. Because Gujarati brocade is so heavy and dense, meenakari work is added to further enhance it. Twill weaving makes the intricate patterns on the saree seem even more amazing.

Design: Instead of the more common weft insertions, circular patterns known as buttis are woven into the field as warp, making them distinctive. When the saree is worn, the buttis look horizontal. Because Gujarati brocade is so heavy and dense, meenakari work is added to further enhance it. Twill weaving makes the intricate patterns on the saree seem even more amazing.

Distinctiveness: Asavali sarees are renowned for their affinity for dyes and vivid colours, as well as for being highly absorbent, lightweight, and buoyant. The usage of floral patterns on coloured silk against gold zari enhances the sarees’ visual appeal. The Gujarati brocade stands out from other brocades because the typical designs have leaves, flowers, and stems that are bordered by a fine, black line, much like inlay work.

Mashru of Mandvi

Mashru (also historically spelled as mashroo, misru, mushroo or mushru) is a woven cloth that is a blend of silk and cotton.

History: Gujarat was India’s first weaving centre for Mashru when it was initially introduced by the Ottoman Turkish Empire in the 16th century. It was mostly weaved in Gujarat, Uttar Pradesh, and Deccan India by the turn of the century. The fabric is mainly manufactured in Mandvi, Gujarat.

Design: Mashru’s designs have gotten simpler over time. The conventional Ikat and Ajrakh patterns and patterned stripes are being replaced with vibrant and vivid designs on solid-colored fabrics. Ikat is combined by artisans with Bandhani saree designs.

Design: Mashru’s designs have gotten simpler over time. The conventional Ikat and Ajrakh patterns and patterned stripes are being replaced with vibrant and vivid designs on solid-colored fabrics. Ikat is combined by artisans with Bandhani saree designs.

Distinctiveness: The cotton interior of Mashru is in direct contact with the skin and has a silk outside. It appears like the creators of this cloth combined all conceivable colors into dazzling compositions. Silk has a shiny appearance on the outside, and the cotton threads on the inside absorb perspiration and keep the user cool in hot temperatures, making cloth useful in India.

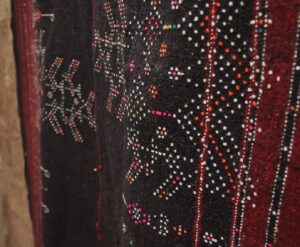

Kutch Weaving

Kutch has rich and varied artistic traditions that converges different cultures and groups.

History: The Marwadi people from Rajasthan migrated to the Kutch region 600 years ago. Due of their expertise in traditional Kutch weaving, they are now referred to as Vankar. Weavers have historically employed wool from the Rabari and Jat pastoral community as well as hand-spun cotton yarn from the Ahir and Patel farming tribes.

Design: The patterns woven into Kachchhi woven fabrics were influenced by the community that used them; they resembled musical instrument shapes, animal herd footprints, etc. The names for motifs like vakhiyo, chaumukh, satkani, hathi, or dholki are evocative of rural images.

Design: The patterns woven into Kachchhi woven fabrics were influenced by the community that used them; they resembled musical instrument shapes, animal herd footprints, etc. The names for motifs like vakhiyo, chaumukh, satkani, hathi, or dholki are evocative of rural images.

Distinctiveness: Using an extra-weft weaving technique, a weft yarn is woven into the loom’s warp to complete the task. The unusual geometric patterns are made by weaving in extra weft. The distinctive, meticulously handwoven designs give Kutch weaving its own individuality. Motifs are woven into shawls. Originally created from indigenous desi wools, they were worn as veils.

Tangaliya of Surendranagar

Dhaba shawls are made by the artisans who live in Rann of Kutch, a semi-desert region. Cotton and woollen yarns are used to yarn the shawls on a traditional loom.

History: Daana or Tangaliya is practised in the Surendranagar district of Saurashtra. It is a unique weaving technique known only to the Dangasia community. They are of five types: Ranraj, Dhusla, Lobdi, Gadia and Charmalia.

Design: Traditional Tangail weaving features wide borders with lotus, lamp, and fish scale motifs. The saris include finely detailed Jamdani designs on Tangail fabrics with a 100s count. Designs are created with loose, twisted white wool. To create a bead-like look, two or three warp threads are needed.

Design: Traditional Tangail weaving features wide borders with lotus, lamp, and fish scale motifs. The saris include finely detailed Jamdani designs on Tangail fabrics with a 100s count. Designs are created with loose, twisted white wool. To create a bead-like look, two or three warp threads are needed.

Distinctiveness: Cotton and woolen yarns are used to yarn the shawls on a traditional loom. To shape the product, a pattern is placed on the loom using threads. The desired color is wrapped immediately on the loom using the rice or starch extraction water. Traditionally, black, yellow, red, orange, and green are used.